The Overlooked Variable: How Overseas Military Service Shapes Veteran Transition

Introduction

In my previous essay, I shared my experience serving in Japan between 2007 and 20111. I wrote about running ekiden races with the base fire department, helping with rice harvests in Yamaguchi-ken, and meeting my wife. I also wrote about the educational limitations I faced, my inability to pursue pre-med courses or moonlight as a cardiovascular technician, and the contrast with fellow service members who felt trapped on “the rock.”

When I returned to the US, I wondered whether spending the majority of my service overseas, and separating directly from an overseas duty station, created transition challenges different from those who served primarily stateside.

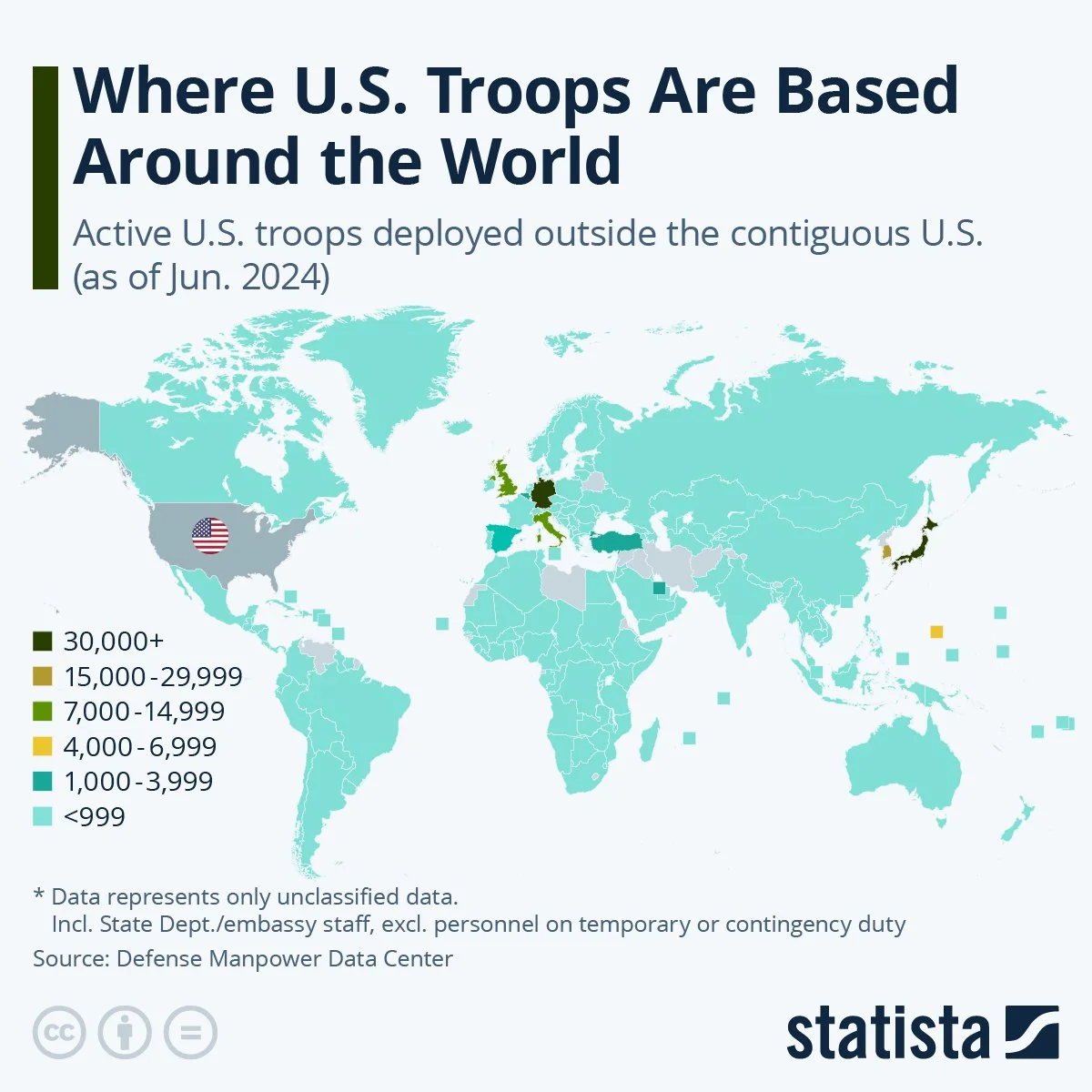

So I dug around online, and what I found surprised me: despite over 160,000 active-duty personnel currently serving overseas, this question appears largely unexamined. This essay lays out the information I could gather and what I couldn't, and questions that emerged.

The Structure of Overseas Military Service

Scale and Distribution

As of March 2025, over 243,000 US military and civilian personnel are stationed in foreign countries. The top five countries are Japan (52,793), Germany (34,547), South Korea (22,844), Italy (12,332), and the United Kingdom (10,046). More than 160,000 active-duty personnel serve outside the United States across 178 countries.

Tour Lengths and Types

Overseas tours fall into two categories: accompanied (family joins at government expense) and unaccompanied (service member goes alone). Standard tour lengths:

Europe and Japan: 36 months

Korea: 12 months unaccompanied, 36 months accompanied

Middle East hardship locations: 12 months unaccompanied

Combat deployments: 6-12 months

Who This Affects Most

The population most affected by overseas service challenges likely includes:

Service members for whom overseas duty represents the majority of their total service

Those who separate directly from overseas assignments without stateside re-establishment

First-termers completing entire enlistments (4-6 years) overseas

Junior enlisted on unaccompanied tours with limited resources

For these service members, overseas isn’t just one chapter. It’s their primary or only experience of adult military life, and they transition to civilian life without ever establishing stateside professional foundations.

Two Very Different Experiences

Overseas service splits into dramatically different experiences:

Type 1: Enriching experience - Higher rank, off-base living, accompanied orders, financial resources to explore. Deep cultural engagement, travel, international relationships, language acquisition.

Type 2: Base-confined experience - Junior enlisted, unaccompanied orders, limited finances. Trapped on base, bars outside the gate, minimal cultural engagement. “The rock.”

What We’re Missing: The Knowledge Gap

I searched for studies examining whether overseas service affects veteran transition outcomes. Here’s what I found:

What exists:

Extensive research on military-to-civilian transition broadly

Studies on employment challenges (75% of veterans experience unemployment during transition)

Research on identity challenges and transition stress

Documentation of TAP limitations

What doesn’t exist:

No studies comparing transition outcomes for veterans who served primarily overseas vs. stateside

No research on how missing years of US network-building affects employment

No examination of educational opportunity costs from overseas service

No investigation of whether separating directly from overseas creates distinct challenges

The one exception: Hiring Our Heroes noted that overseas service members face logistical challenges (time differences, FPO addresses) when job-searching from abroad. But this addresses logistics, not long-term effects.

What Might Matter: Challenges Unique to Overseas Service

The Network Deficit

Military service already creates intense social bonds where coworkers are friends. Overseas amplifies this. You’re even more isolated from civilian social circles. Your entire professional network becomes military-only.

The challenge: While stateside peers spent years building civilian professional contacts, regional market knowledge, and industry connections, overseas service members built none of that. They return to the US starting from zero.

Upon separation: Fellow overseas service members scatter across the country. International friendships stay abroad. There are no local civilian professional contacts because none were ever built.

For someone who spent 4 years overseas and separates directly from that assignment, this means entering the civilian job market with literally no US professional network as an adult.

Missing Educational and Professional Opportunities

Overseas duty stations lack:

Specialized courses (pre-med, laboratory sciences, technical training)

Moonlighting opportunities common stateside

Internships and apprenticeships

In-person engagement with US educational institutions

Exposure to civilian work culture

The opportunity cost: Years when stateside peers were building credentials, civilian work experience, and professional skills. Approximately 75% of veterans experience unemployment during transition, with almost one-third spending 6+ months looking for work. These gaps may compound that challenge.

The Lifestyle Gap (For Enriching Experiences)

Service members with enriching overseas experiences lived lifestyles they can’t afford as civilians. Living in Tokyo, traveling Europe, experiencing diverse cultures on military pay with housing allowances and travel benefits.

Upon separation: Replicating that lifestyle as a civilian costs far more than most veterans can afford. This gap may drive career decisions, salary expectations, and geographic choices in ways that haven’t been studied. It may also contribute to dissatisfaction with “ordinary” civilian life, especially for those from rural backgrounds.

The Compound Disadvantage (For Base-Confined Experiences)

Junior enlisted on unaccompanied tours, especially in operational commands, faced:

Extreme social isolation and base confinement

Limited healthy outlets beyond bars outside the gate

Financial constraints preventing cultural exploration

Strict SOFA restrictions

High operational tempo

These conditions are associated with disciplinary problems, alcohol dependence, sexual trauma, and mental health crises.

The compound disadvantage: This population missed all the stateside opportunities (education, professional development, networks) while also gaining none of the cultural enrichment benefits. They spent years in a foreign country but remained culturally isolated. They return with neither the professional foundation of stateside service nor the cultural assets of enriching overseas experience.

Intensified Military Bonds and Their Loss

Overseas service may create even stronger military bonds than stateside service due to shared isolation. Upon separation, these intensified bonds may be harder to lose, yet more difficult to maintain due to greater geographic dispersion.

Whether this creates measurably more difficult transitions remains unexplored.

Why This Matters

Current transition programs treat all separating service members essentially the same. TAP doesn’t differentiate between someone separating after 20 years with 3 years overseas mid-career, versus someone separating after 4 years spent entirely overseas.

If overseas service as a proportion of total service matters, particularly when it’s the final duty station, then we’re potentially missing something significant for a substantial population.

Questions worth investigating:

Do veterans who spent the majority of their service overseas have different employment outcomes?

Does separating directly from overseas without stateside re-establishment affect time to employment or job satisfaction?

How do missing years of US network-building compound with other transition challenges?

Does the educational and professional opportunity cost create measurable career trajectory differences?

Do the two types of overseas experience (enriching vs. base-confined) produce different transition outcomes?

Conclusion: A Question Worth Asking

I don’t know whether overseas service creates measurably different transition outcomes. I couldn't find much information or data online. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe the effects wash out, or the positives offset the negatives. Maybe this has always been the case and it’s not actually a problem.

But the structural differences are real: missing years of network-building, educational limitations, professional opportunity costs, and either extraordinary lifestyle loss or compound disadvantage from isolation. For service members who spent the majority of their service overseas and separated directly from overseas assignments, these aren’t minor variables.

Current transition programs don’t account for these differences. If overseas service matters, we’re missing opportunities for targeted support. If it doesn’t matter, that would also be useful to know.

The question seems worth asking: For veterans who spent most of their service overseas and transitioned directly to civilian life from overseas duty stations, does this create distinct challenges that current programs don’t address?

Given how many service members this affects, maybe we should find out.