Rebuilding a Civilian Life: How I Used What Was in Front of Me

Photo by Abolfazl Ranjbar

Veterans often hear the same advice: use your resources, build your network, get involved. It sounds right, but it’s vague. Which resources? What kind of involvement? And how do you know if any of it will actually matter later?

•••

For most of us, the link between what we do day to day and what becomes opportunity isn’t clear until much later. You only see it when updating a resume, when a small volunteer project or student group suddenly reads like a meaningful line that signals credibility and momentum.

For someone like me, with limited familial resources, it has been essential to lean on every form of support I could qualify for. These programs and communities aren’t secret. They are usually one Google search, one coffee chat, or one online platform away.

I’ll quickly mention that I fully align with a common advice that newly separated veterans should give themselves as much time as they can afford to decompress and figure out what they want and why. Without that clarity, either a) one doesn’t know what support to even look for or b) everything looks useful so one ends up scattering their time and energy.

But once you can name your direction, your goal, you can filter out the noise and invest energy where it counts. The following is my account of how I have been able to find and gather resources, network, and capitalize on my efforts to achieve my goals. It is not a blueprint, but an example of how structured programs, informal communities, and personal relationships can quietly combine into a system of progress.

Education

From the moment I realized I have to do whatever I can to prepare for civilian life, I used Tuition Assistance to take online and on-base courses through the University of Maryland Global Campus. It was my first contact with higher ed. It gave me early credits and confidence, one intro course at a time. One more to note here is that as a first-generation college student if I didn’t know anything about higher-ed, one thing I was certain of is that I need to work hard to manage my GPA if my goal was to transfer to another four-year. That meant that I take only as many classes as I can handle. Taking classes while in uniform isn’t easy. Your job being a top priority isn’t something that can be negotiated or questioned. It also meant that I quickly drop a course if mission got in the way. I digress.

A few years later when I was re-assigned to Japan, in U.S. Naval Hospital Okinawa, I started looking for ways to make my technical training count. Navy COOL funded my cardiovascular-tech credentials to civilian licenses. The ACE/SMART transcript system converted my “C School” coursework into college credit. That translation mattered—it made my record legible to universities or careers that often overlook military learning.

After separation, I enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin using the Post-9/11 GI Bill. My first stop on campus was Student Veterans Services, which helped me navigate benefits and introduced me to other veterans. I received travel grants, met mentors, and later served as a peer mentor myself. The office became my logistical and social anchor in a state university of 50,000 students.

During undergrad I also used the VA VITAL Program, an on-campus mental-health service connecting veterans to clinical care. It provided stability while I balanced classes and part-time work.

Through campus student vet activities I got to learn about Student Veterans of America, a major nonprofit in the veteran higher ed space. Attending SVA conferences helped me understand the broader landscape of higher education among veterans — the policies, gaps, and nonprofit/government/corporate partnerships shaping how we transition into academic life. I later presented at the national SVA conference as a way to contribute back to that same community.

The Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program changed my trajectory entirely, which I found through a Google Search at the beginning of second semester at UT. The question I asked myself was, is there a program where I can get help with grad school admissions? Sure enough, there was. Upon acceptance, it provided research funding, faculty mentorship, and a clear framework for pursuing graduate study. Through McNair, I learned how graduate admissions actually work: how to position research interests and navigate Ph.D. applications. I also became part of a small cohort of sharp, driven peers whose intellect and dedication never failed to impress me.

I made a point to attend office hours whenever I could. Conversations I had with faculty developed into a relationship that felt more like a peer collaboration, where shared curiosity and research eventually led to a co-authored paper in Armed Forces & Society and presentations at national conferences. Each step—grant, publication, presentation—was both a formative experience and a visible signal, each one reinforcing the next.

Outside of academics, I joined a local running club. Training for the 2018 Houston Marathon and running a 2:42 personal record kept me grounded. The discipline of running became another network, people who were goal-oriented, balanced, and supportive. Those communities often teach lessons that later translate into professional life: endurance, pacing, and habit.

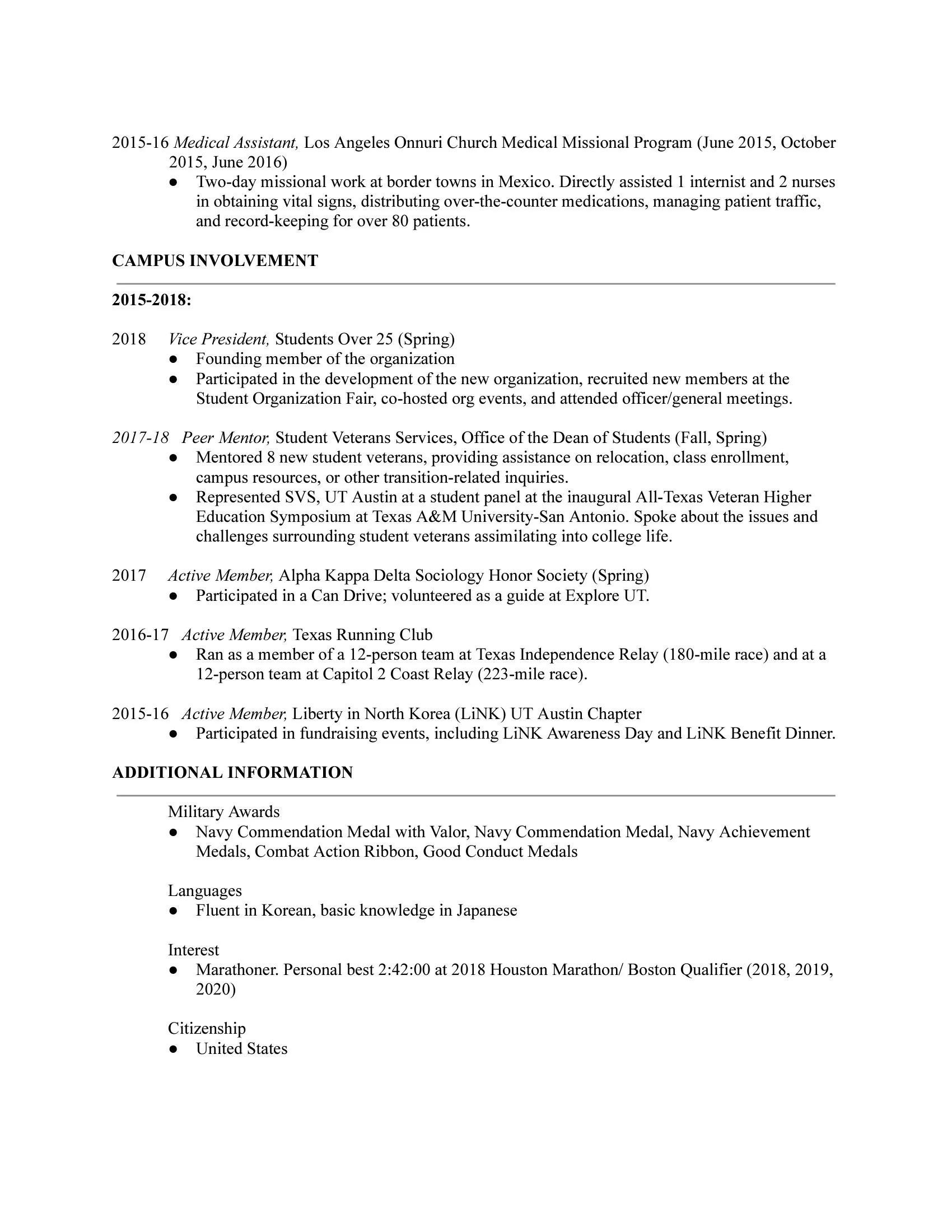

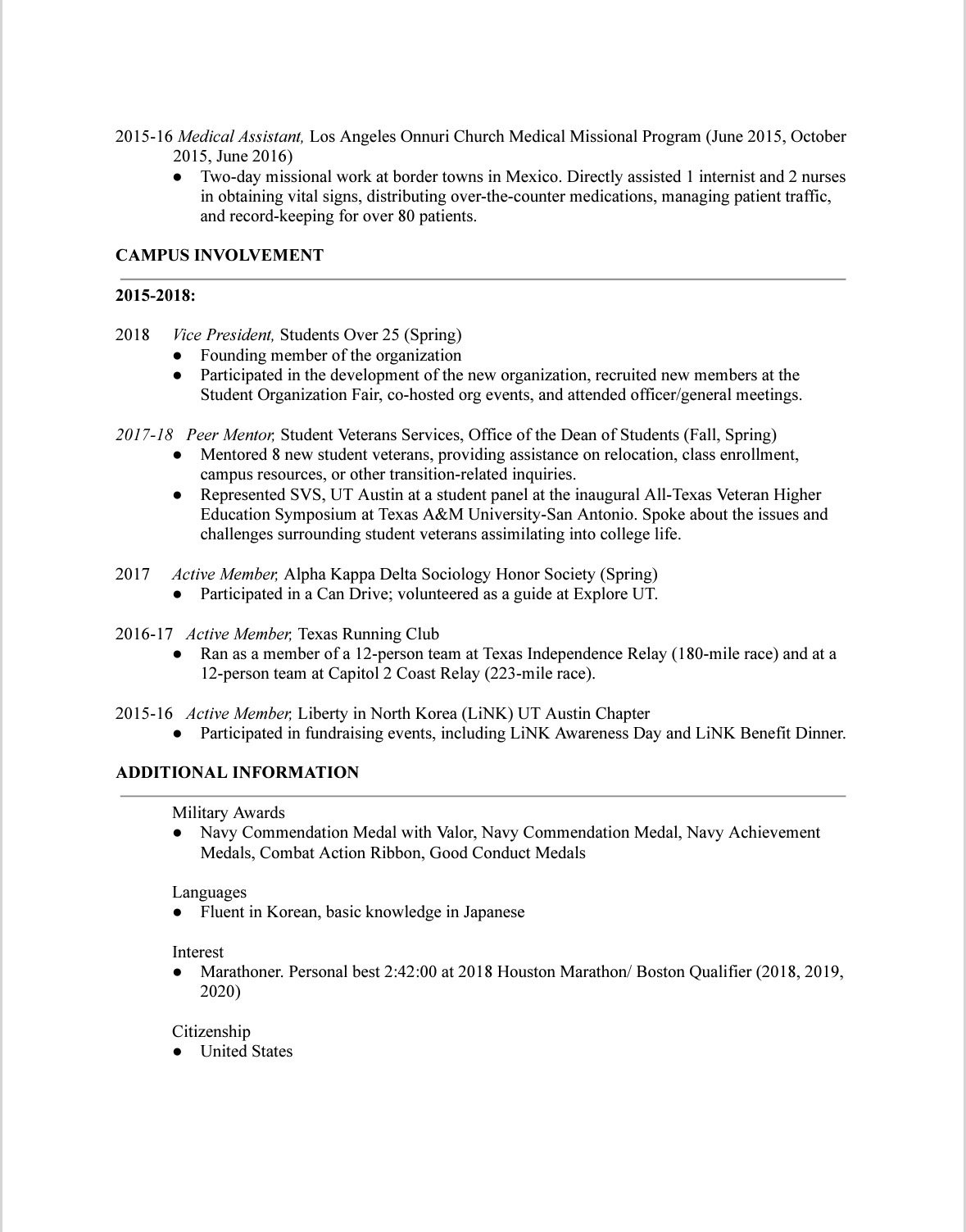

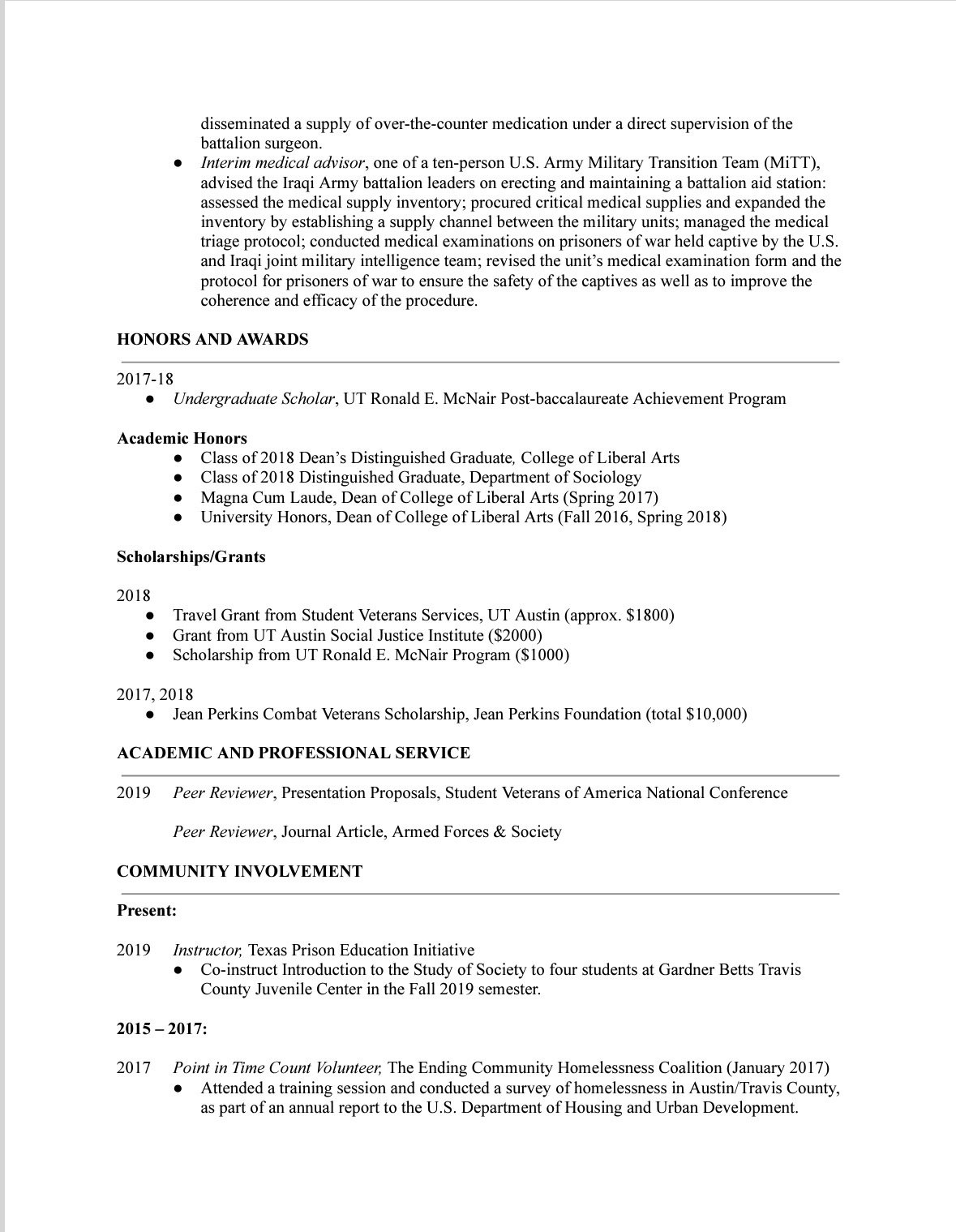

Curriculum Vitae, 2015-2019

Career

All the support I received during undergrad—scholarships, mentorship, and research opportunities—culminated in my acceptance to one of the top doctoral programs in the country. My goal of pursuing advanced study had come true.

I stayed at my alma mater for grad school, where teaching and research deepened my understanding of institutions and human behavior. After two years, I realized that academia wasn’t where I wanted to stay. What I did take from it, though, was a clear sense of how my training in qualitative research, systems thinking, and storytelling could apply beyond the university.

Austin’s growing tech scene made that realization tangible. Many of my friends and mentors were working in design, product, and data roles. Their paths made me curious about how my background might translate. That curiosity led me, in 2021, to take part-time design and visual-communication courses at Austin Community College—a deliberate pivot toward creative, applied work.

Around the same time, I joined the Austin Asian Resource Center as a part-time community outreach and marketing specialist. I couldn’t have known about this role had I not interned there three years prior. The role turned out to be more than a job; it was my first lesson in how storytelling and design shape public engagement.

That experience reinforced my affinity for mission-driven work and public service, which in turn led me to look for design opportunities within the government sector. Around that time, I discovered the field of civic technology and began volunteering with Code for America and its local chapter, Open Austin.

Though unpaid, they connected me directly with designers, developers, and public servants tackling real problems through open data and design. Each collaboration made the field feel more accessible and showed me how to frame my sociological background as a design asset.

To strengthen my footing in industry, I joined American Corporate Partners (ACP), where I was paired with a design executive from the private sector for a year-long mentorship. I found out about this program through VA Newsletter I actually do take time to read. That relationship helped me reframe my experience for corporate audiences and shift my language from describing tasks to communicating impact.

In parallel, I found out about a remote internship program called Virtual Student Federal Service (VSFS) through a Slack channel for design students.

An academic year-long program, this became my first hands-on exposure to digital work in the federal space. That experience, combined with the civic-tech projects, expanded my professional network in government technology and gave my resume a signal that later proved decisive.

By the fall of 2021, these pieces finally came together. A design faculty member, whom I met at her virtual talk, introduced me to a hiring manager at a design consulting firm serving defense and government clients.

By then, I had a career story that felt natural to me: I was a qualitative design researcher and advocate for public good who understood bureaucratic systems and could navigate them with ease. My resume and interviews told the same story—one shaped by years of divergent, yet deliberate and cumulative steps.

Not long after, I was hired to support a federal digital-transformation initiative during the ARPA investment wave. The connection wasn’t accidental; it grew out of overlapping networks—veteran programs, civic-tech communities, and mentors who knew how to translate military discipline into public-sector innovation.

I found most of these opportunities through faculty connections, online searches, student Slack channels, and veteran social networks. Some appeared by chance; others through persistence. For nearly every goal I pursued, there was someone who had walked that path before and was willing to help. The key was finding where those people gathered, which almost always happened through friendships and professional relationships built over time.

Not every effort paid off immediately. Many didn’t at all. But I pursued them because they were interesting, educational, and valuable in their own right, while loosely aligning with my broader goals. That made them worth completing, even when outcomes weren’t certain. Afterward, it was on me to translate those experiences into the next step forward.

Self-Care

Professional and academic work burn energy quickly. Programs like VA VITAL and the Veterans Health Administration kept me tethered to consistent mental-health and medical support. The running community filled the same role socially. Training offered a rhythm familiar from service life—structured, measurable, and communal.

Later, I participated in Honor Flight, which reconnected me with the broader veteran community and offered perspective on continuity.

These activities might not look like “career moves,” but they’re the infrastructure that keeps long-term growth sustainable. Without that baseline, no credential or opportunity would have mattered.

Signals and Communities

Looking back, every organization I joined functioned both as a signal and as a community.

When I joined McNair, I wasn’t just earning a research credential; I was entering a culture that valued inquiry and academic rigor. When I volunteered with Code for America, I wasn’t just adding a civic-tech project; I was learning a new professional dialect. When I ran marathons, I was joining a network that treated discipline and incremental progress as virtues.

Each of these spaces taught me how to be legible to new audiences. Over time, knowing how to show competence across different systems became its own form of capital.

A signal is visible. It’s the scholarship, internship, or affiliation others recognize instantly. It’s shorthand that says, “I’ve operated successfully in this space.” But a signal is only the surface layer.

Beneath it lies the community that produced it: the mentors, peers, and shared values that shaped your understanding of how the world works. To every opportunity, I can put a name and face of those who opened doors.

Eventually, I stopped thinking of myself only as a recipient of opportunity. I began looking for ways to help others navigate the same systems, sometimes formally through organizations like SVA or Student Veterans Services, sometimes informally through one-on-one conversations.

I try to be the person who makes those connections visible for someone else. The same way others did for me.

Closing

“Use your resources” is easy to say but hard to visualize. In reality, resources are not isolated; they are gateways into overlapping networks of people and shared values.

I have been fortunate to receive generous support from people and programs along the way. That support did not come automatically. It took effort to find and courage to accept. It required creative thinking, a willingness to be vulnerable, and the humility to ask for help. Most of all, it required learning to see what I already had and how I could use it.

The work begins with finding footing. Start where you are today. Figure out what you have, what you want to do, and why. Once you know that, you will start to see what is missing. Then you can search for those missing pieces, or create them.

Each program I joined began as a way to stabilize my life after service. Over time, the people I met through those programs became friends and colleagues I could lean on, and who could lean on me. The resume lines make you visible, but the people behind them keep you moving.

It was never clear how any of these efforts would turn into opportunity. My career has been anything but linear or predictable. With each goal—earning a degree, finding work, pivoting into design and operations—I have been able to look back and see how earlier experiences fit together. It is like building with Lego. I take the pieces I already have and arrange them into a narrative that feels both authentic and relevant to the audience I am speaking to.

If I cannot connect what I have done to where I am heading, I do not pursue it. That standard keeps me honest and focused.

Every one of these experiences leaves a mark. They shape how you see the world, the shortcuts your mind takes, the tone of your speech, and even your tastes. Over time, they do not just build a resume. They build you.

Resource & Program

| Category | Program | Function / Type | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education Access | Tuition Assistance | Tuition funding for active duty | dantes.doded.mil |

| Education Translation | ACE / SMART Transcript | Military-to-college credit evaluation | acenet.edu |

| Campus Support Network | UT Student Veterans Services | Advising, funding access, programming, advocacy | utexas.edu |

| Academic Community | Student Veterans of America (SVA) | Chapters, advocacy, leadership, conferences | studentveterans.org |

| Academic Advancement | Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program | Research funding, graduate prep | ed.gov |

| Peer Scholarship / Inquiry | Independent / Organic Research Projects | Concept development, writing, inquiry practice | |

| Affiliation & Representation | Asian Veteran Engagement Group | Community, research, identity-based support | |

| Career Discovery | CareerOneStop | Career exploration, labor market information | careeronestop.org |

| Career Translation | Navy COOL | Credentialing and license funding | cool.osd.mil |

| Mentorship & Networking | American Corporate Partners (ACP) | 1:1 executive mentorship, private-sector exposure | acp-usa.org |

| Civic-Tech Entry | Virtual Student Federal Service (VSFS) | Remote federal internships, networking | vsfs.state.gov |

| Civic Innovation | Code for America / Open Austin | Civic-tech projects, portfolio building, volunteer & paid work | codeforamerica.org |

| Health & Wellness | Veterans Health Administration | Comprehensive healthcare access | va.gov/health |

| Mental Health & Reintegration | VA VITAL Program | On-campus mental health and transition support | va.gov |

| Physical Wellness | Local Running Club | Fitness, structure, informal network | |

| Recognition & Remembrance | Honor Flight | Recognition travel, veteran honor & connection | honorflight.org |